1. Tools, Focus, and the Pursuit of Depth:

Since the beginning, humanity’s defining strength has been its relentless pursuit of knowledge and mental sharpness. Picture the hunter, eyes narrowed, tracking prey, the craftsman chiselling marble, the scholar poring over ancient manuscripts. Each figure is bound by a common thread: the capacity for deep focus, the ability to lose themselves in the pursuit at hand. This gift of concentration—this full immersion in a task—has shaped our very evolution: driving us to reach further, think sharper, and discover more.

And it’s also true, I think, that this drive, this Nietzschean self-overcoming, has only intensified. We’ve built institutions devoted to sharpening our mental faculties—law schools, music conservatories, medical academies, and business programs—all designed to give students an edge in an increasingly complex and competitive world.

To aid us in this pursuit, we’ve developed various tools that extend and enhance our thinking. Visual aids simplify complex ideas. Smart devices manage our schedules and store our memories. And now, artificial intelligence sifts through oceans of data, revealing patterns and insights once hidden.

Yet, perhaps no tool has shaped us more than literacy. Five thousand years ago, the advent of the written word freed us from relying solely on memory, enabling us to record, organise, and share knowledge across generations. Writing didn’t just preserve our thoughts; it transformed them, allowing us to collect, analyse, and build upon ideas in ways that were previously inconceivable.

Even early readers noticed the power of this shift. The medieval bishop Isaac of Syria described reading as a dreamlike state where the mind finds focus and clarity. “Like being in a dream,” he wrote, “my senses and thoughts become intensely focused. As the quiet persists and the chaos of my daily struggles subsides, clarity takes over, and a delightful stream of unending thoughts fills me.”

His description captures what what many of us still feel: when fully absorbed in a book, the world fades away, and our mind enters into a realm of deep engagement. In this state, connections form, insights emerge, and ideas flow freely: we interpret, infer, and engage with the text on multiple levels, uncovering insights hidden between the lines.

Writing has given rise to structured knowledge and critical inquiry in the realms of science, history, and philosophy. Beyond that, it has enriched our experience of art, language, and storytelling—letting us explore complex narratives and abstract ideas that oral traditions alone could never support. Writing is so integral to our thinking that we often overlook the subtle, transformative ways it has shaped how we understand the world.

“At first, the thrill of learning to read is all about grasping how letters form words and how those words form meaning. But soon we begin to ask what else those marks on a page can give us. We begin to want information, entertainment, invention, even truth and beauty.”

—Francine Prose | Reading Like a Writer

This article will explore that profound impact. We’ll uncover how writing has brought permanence to human thought, allowing ideas to outlast their authors and ripple across centuries. We’ll see how it has created a collective memory, one we can critique, refine, and reimagine. And we’ll examine how writing has deepened our capacity for reflection, helping us revisit old insights and question the fabricated truths we’ve inherited.

But there’s more. As digital technologies reshape our mental landscape, new questions emerge. Information now flows faster than ever, but our engagement with it is often fragmented. We skim, scroll, and swipe—taking in more, but contemplating less. It’s worth asking: are these technologies deepening our understanding, or are they diminishing our ability to reflect? What do we value most in our intellectual lives—quick consumption or thoughtful contemplation?

2. The Power and Limits of the Spoken Word:

Before writing was invented, knowledge was a living, breathing thing, sustained in the mind and passed down through speech. Mankind relied on memory, sketches, and music to preserve what mattered. But therein lay a fundamental problem: the human brain, for all its power, is fallible. As psychologists and linguists remind us, our brains are wired to capture experiences, not details. The truth is, like it or not, events blur, timelines shift, and emotions warp recollections, distorting reality and twisting the truth.

Despite these limitations, early humans found ingenious ways to overcome memory’s imperfections. They relied on emotionally charged tales and melodies, embedding essential knowledge into oral traditions. Songs became libraries; stories served as archives. Laws, legends, wisdom—all woven into verse, designed to be recited and remembered, transformed into a shared cadence that carried knowledge across generations.

Nowhere was this more evident than during the twilight of the Late Bronze Age Collapse around 1250 BC, when Homer’s epics, The Iliad and The Odyssey, became touchstones for cultural revival. Passed down through generations, these stories evoked the memory of a lost Golden Age of Mycenaean Greece—celebrating ideals like arete (excellence) and kleos (glory). Through Homer’s verses, the fragmented Greeks began to see themselves as a unified ethnos, linking their present struggles to a storied past.

What emerged was a cultural blueprint—a shared lexicon and set of references that reflected and reinforced Greek identity. Recited in communal gatherings, the rhythm and cadence of these verses imprinted moral and social values onto the minds of listeners. To be Greek meant pursuing excellence, seeking immortal glory, and belonging to a broader ethno-cultural heritage.

A striking example is found in the actions of the Spartan general Callicratidas during the Peloponnesian War. Advised to retreat before a superior Athenian fleet, he refused, declaring, “To flee is a disgrace and an injury to Sparta. No; to stay here, be it death or victory, is best.” His choice to stand and fight, despite the impossible odds, was drawn in no small part from the same sense of hopeless duty and courage displayed by Hector in the defence of Troy. Like Hector, Callicratidas upheld Greek values not because he expected to win but because to abandon them would mean a defeat of spirit.

“No man escapes his fate, neither brave man nor coward. I was born for war, for pain and slaughter. My fate is here, Andromache, let me fulfil it. Though you grieve for me, I ask you to rejoice in the knowledge that I died doing what I was born to do. And if the Trojans win, you will hear it said that Hector, son of Priam, held his ground to the last."

— Homer | The Iliad

Yet, while oral traditions excelled at conveying moral themes and emotional truths, they fell short on detail and precision. As Walter Ong points out in "Orality and Literacy," ancient cultures possessed an emotional and intuitive depth that is perhaps elusive to modern literate societies. Yet, this depth came at a cost. The need for vivid, memorable storytelling left little room for complexity and analytical depth. Handling large amounts of data simply wasn’t possible; the stories, for all their power, traded precision for impact.

The advent of writing changed everything. For the first time, knowledge could exist beyond the moment of its expression. Homer’s epics, once fluid and ever-shifting, became fixed texts—ready to be read, analysed, and preserved for future generations. Writing liberated ideas from the constraints of memory, making them open to critique, debate, and refinement.

“My mother tells me that there are two ways in which I may meet my end. If I stay here and fight, I shall not return alive but my name will live forever; whereas if I go home my name will die, but it will be long ere death shall take me. To my mind, then, I shall not stay here; my heart will not be content until I have made my way to the land of my fathers."

— Homer | The Iliad

This permanence transformed Greek culture. It allowed for the codification of laws, the documentation of histories, and systematic exploration of ethics, science, and philosophy. Homer’s tales, once the unifying force of a fragmented people, became the bedrock of classical Greek civilisation—sparking debates and shaping ideas that would echo through the ages. But, as is often the case, I’m getting ahead of myself.

3. Rewiring the Mind—The Birth and Impact of Written Language:

Writing began humbly around 8000 BC, when nomadic pastoralists etched simple symbols into clay tokens to keep track of livestock and goods. At first glance, these marks—mere scratches and lines—seem unremarkable. Yet they marked a seismic leap in human evolution. For the first time, knowledge existed outside the human mind. Information could be recorded, shared, and interpreted by others. What began as a practical system for counting sheep and measuring grain laid the groundwork for the literature, history, and philosophy we now take for granted.

“Like most—maybe all—writers, I learned to write by writing and, by example, by reading books. I can remember the novels and stories that seemed to me revelations: wells of beauty and pleasure that were also textbooks, private lessons in the art of living.”

—Francine Prose | Reading Like A Writer

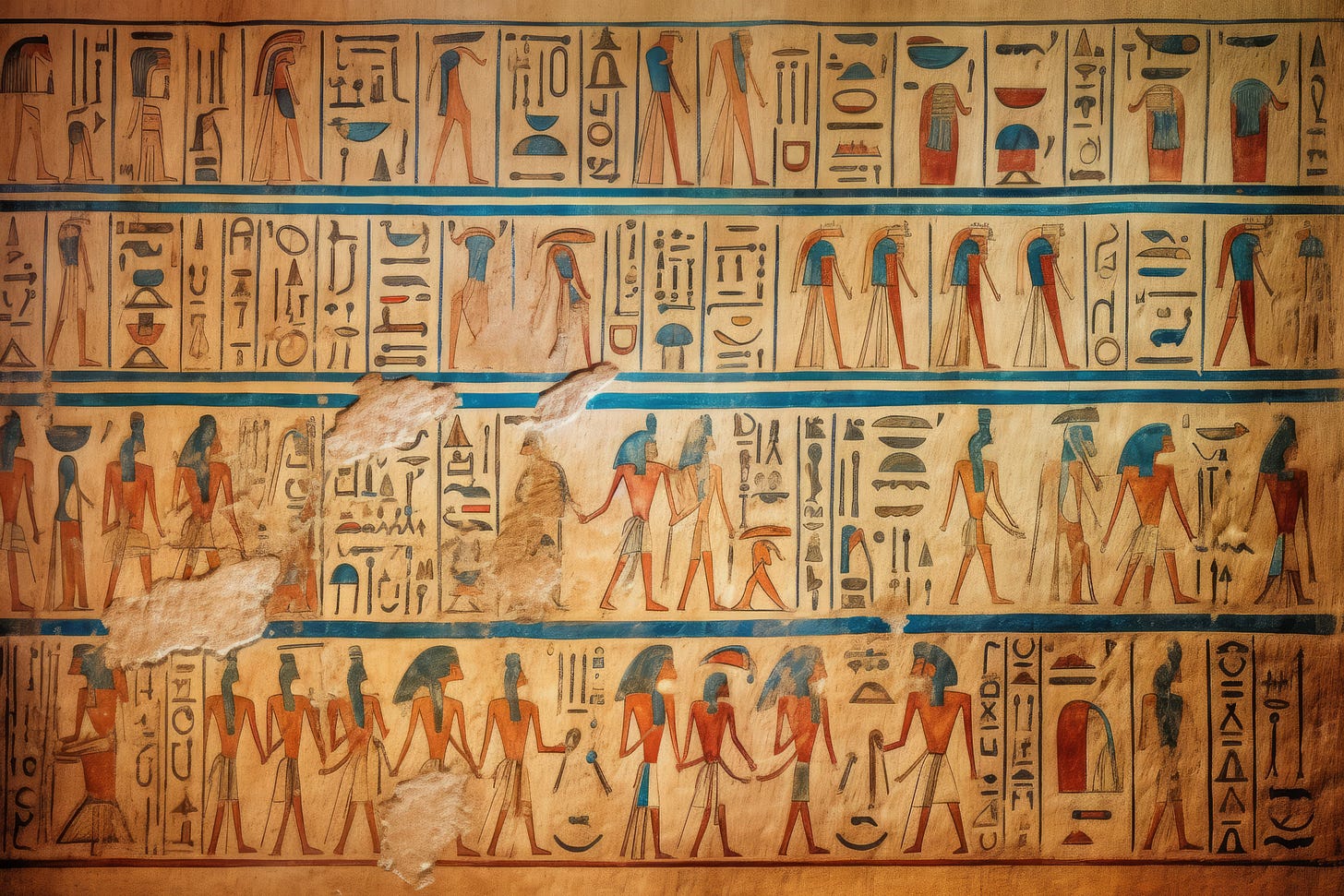

As writing evolved, so did its complexity. By the end of the fourth millennium BC, those simple marks had transformed into sophisticated scripts like Sumerian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphics. These writing systems went beyond merely representing objects—they expanded to include hundreds of characters capable of capturing sounds, ideas, and abstract concepts. Mastering them demanded formidable mental effort. The human brain had to forge new neural pathways, integrating vision, language, and spatial reasoning in ways that stretched cognitive boundaries.

Developmental psychologist Maryanne Wolf, in her book Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain, describes how these new neural circuits “literally crisscrossed the cortex,” rewiring our minds for an intricate dance between sight, sound, and meaning. And this underscores an important truth: Reading and writing were not innate human skills—they required immense concentration and training, which, in turn, made literacy an elite privilege. Only those with the resources and leisure to master this art could wield the influence that came with it.

For writing to become a tool of the masses, it had to evolve further—becoming simpler and more accessible. This democratisation took root in the aftermath of the Bronze Age Collapse. And, as history would have it, it was the Greeks, scattered among the ruins of once-mighty palaces, who would bring this transformation to life.

4. The Phonetic Alphabet and the Rise of Greek Genius:

“In all history,” writes Betrend Russel in his 1946 magnum opus, The History Of Western Philosophy, “nothing is so surprising or difficult to account for as the sudden rise of civilisation in Greece. What they achieved in art and literature is familiar to everybody. But what they did in the purely intellectual realm is even more exceptional. They speculated freely about the nature of the world and how we might go about living, without being bound in the fetters of any inherited orthodoxy. What occurred was so astonishing that, until very recent times, men were content to gape and talk mystically about the Greek genius.”

Picture the scene: It's around 750BC—a sun-bronzed Greek merchant, fresh from trading voyages, shares stories of a Phoenician script used to keep records. An elder, weathered and grey, carves these foreign symbols into clay, his calloused hands moving with deliberate care. Around him, younger men gather, their pale eyes bright with curiosity, their classical features sculpted and striking. They observe intently, then lean in to experiment—adding vowels to the consonants, transforming these marks into a script that mirrored the cadence of their own speech.

In that moment, the Greek phonetic alphabet was born. It revolutionised writing, liberating readers from the burden of interpreting meaning through context. Words could be read and pronounced as written, eliminating ambiguity and making literacy more accessible. Unlike intricate logograms that required immense mental effort to decode, phonetic reading was intuitive, seamlessly matching letters to sounds with elegant simplicity.

The consequences were profound. What had begun as a practical record-keeping tool evolved into the cultural scaffolding of a vibrant new intellectual world. Bertrand Russell had every reason to marvel.

5. How Spaces and Punctuation Changed Reading Forever:

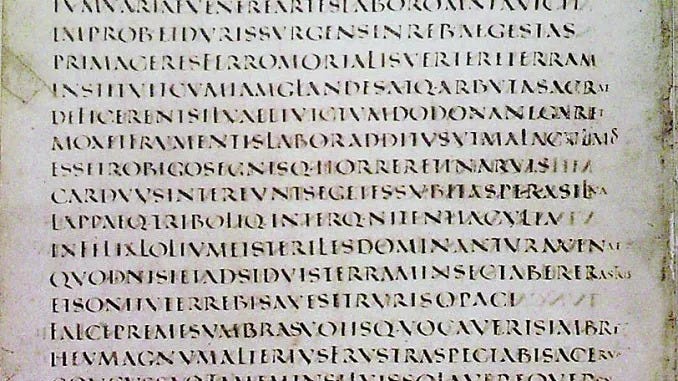

Despite the leaps forward in early writing, these scripts still bore the imprint of their oral roots. One telling feature was scriptura continua—a style where words flowed together without breaks, mirroring the uninterrupted cadence of speech rather than how language is visually parsed.

John Saenger, in "Space between Words," describes how readers of these dense passages laboured to extract meaning, often pausing, backtracking, and puzzling over where one word ended and another began. To make sense of the continuous stream of text, words tended to be spoken aloud, reinforcing their deep connection to speech.

Saint Augustine, around AD 380, captures this vividly in his Confessions. He recounts his astonishment at witnessing Ambrose, the bishop of Milan, reading silently—an act so unusual that it seemed almost magical. Augustine marvelled at how Ambrose’s eyes moved across the page, absorbing meaning without the aid of vocalisation. At the time, silent reading was an exception; the norm was to vocalise, using sound as a bridge to comprehension in a world without clear visual boundaries. Reading was akin to solving a complex riddle, engaging parts of the brain responsible for problem-solving and decision-making.

The fall of the Roman Empire marked another chapter in the evolution of writing. In the quiet monasteries of 6th- and 7th-century Ireland and England, religious scribes began breaking words apart, making sentences visually navigable. By the 13th century, punctuation had become commonplace, and the dense, continuous scripts of the past were giving way to more navigable formats. As writing evolved to include spaces and punctuation, reading transformed into a private, contemplative act, opening the door to a more intimate engagement with the written word.

“He writes a great deal. He codifies everything. Information is power. Technical theory is victory. He intends to compile and systemise it all. When the war is done, perhaps, he will have time to properly compose his archives of data into some formal codification.”

—Dan Abnett | Know No Fear

Writers, too, adapted. Freed from the constraints of dictation, they found room for creativity and self-expression. Guibert of Nogent, a Benedictine monk, exemplified this shift. In solitude, he explored unique scriptural interpretations, recorded dreams in striking detail, and even ventured into erotic poetry—tasks he would never have dared attempt with a scribe present. Later, when failing eyesight forced him to dictate his writings, he mourned the loss of independence, longing for the days when he could write “only by voice, without the hand, without the eyes.” Writing had become a deeply personal act, a tool for introspection and exploration.

"The ability to situate your writing, tie threads together into larger themes and tapping into the emotional connotations behind those threads, using them as launch pads to explore and challenge abstract ideas, is what creates good writing"

— William Zinsser | On Writing Well

And as authors shifted to private writing, they also began to extensively revise and edit their works. John Saenger highlights that for the first time, writers could review their work as a whole, refine arguments, and eliminate redundancies. This led to clearer, and more sophisticated texts. By the late 14th century, manuscripts often featured paragraphs, chapters, and tables of contents, guiding readers through increasingly complex ideas.

Yet, for all their advancements, books remained rare and expensive. The rich intellectual culture they cultivated was still confined to the elite. Though the written word had found its ideal form in the book, another revolution was needed—one that would make books affordable, mass-produced, and accessible to everyone.

6. Mainz, 1450—The Invention That Changed History:

Imagine stepping into a 15th-century workshop in Mainz, Germany. The air is thick with the scent of molten metal and the sharp tang of oil-based ink. Before you stands Johannes Gutenberg, carefully pouring liquid metal into tiny, precise moulds. His focused intensity radiates like the heat from a fire. Nearby, the wooden-screw press groans and creaks. With a firm pull of the lever, inked letters kiss the paper, producing a flawless page in seconds—a feat that once took scribes months to achieve. Gutenberg’s smile flickers, warm and bright as molten magma. In that moment, he realises he is about to bring books to the masses.

“He is a genius. He is a wordsmith: a distiller of ideas and images into a language which makes what he thinks and sees live in the minds of those who have never seen or dreamed of anything beyond their own lives. But that is not the true core of his quality. He sees a future of truth and illumination, and reaches to create it with his every deed. The Imperium we’re fighting to create will be held together by the words and ideas of men like Sigismund Voss.”

—John French | Praetorian of Dorn

Francis Bacon understood the gravity of this innovation. In his 1620 work Novum Organum, he ranked the printing press alongside gunpowder and the compass as inventions that reshaped civilisation. He marvelled at how it “changed the face and condition of things all over the world.” And indeed, the change was staggering: Books became affordable and widely available. In Florence, for instance, a printer could produce over a thousand copies of Plato’s Dialogues for the cost of three florins—what a scribe would charge for a single handwritten copy. Within fifty years, as many books were printed as had been hand-written in all of Europe over the previous millennium.

Printers didn’t just publish new works; they resurrected classical texts, making them available in both original languages and translations. This flood of printed material reshaped the very structure of society’s cultural and intellectual landscape. Harvard historian Robert Darnton described the emergence of a “Republic of Letters,” open to all who could read and write. The realm of books, once locked away in monasteries and academic circles, had been thrown open.

7. The Printing Press and the Birth of Modern Thought:

The ripple effects were indeed profound. The English vocabulary exploded from a few thousand words to over a million, as the flood of books created a hunger for new concepts and expressions. Language itself evolved, unlocking expansive new realms for thought and creativity.

Writers began to experiment boldly, reshaping sentence structures and playing with word arrangements to reflect the complexity of human experience in ways never before imagined. Readers, now more engaged and reflective, found themselves exploring these new literary landscapes, interacting with ideas that deepened their understanding of the world. This exchange between writer and reader elevated the collective consciousness, transforming reading into an experience far deeper than the mere act of processing words on a page.

“Perhaps my taste in reading had something to do with the limitations I was discovering, day-by-day: the brick walls of time and space, science and probability, to say nothing of whatever messages I was picking up from the wider culture.”

—Francine Prose | Reading Like A Writer

Elizabeth Eisenstein, in “The Printing Press as an Agent of Change,” noted that these literary pioneers transformed readers, making them more observant and sensitive to the complexities of human experience. Books became a means of sharpening awareness, much like the way artists or musicians make us see and feel the world more vividly.

Scientific research on brain plasticity backs up these claims. The synaptic pathways strengthened through reading and writing are not limited to literacy; they enhance other cognitive skills as well. Engaging deeply with complex narratives and arguments helps to support creativity, reflection, and adaptability. Maryanne Wolf highlights that a brain shaped by sustained reading becomes more agile, better equipped to generate new ideas. These intellectual “muscles” also improve decision-making and build mental resilience, demonstrating the far-reaching power of the written word.

Wallace Stevens encapsulates the magic of this engagement in his 1946 poem The House Was Quiet and the World Was Calm. His lines don’t just describe the act of immersive reading; they make you experience it:

“The house was quiet and the world was calm. The reader became the book; and summer night was like the conscious being of the book. The house was quiet and the world was calm. The words were spoken as if there was no book, except that the reader leaned above the page, wanted to lean, wanted most to be the scholar to whom his book is true, to whom the summer night is like a perfection of thought.

The house was quiet because it had to be. The quiet was part of the meaning, part of the mind—the access of perfection to the page. And the world was calm. The truth in a calm world, in which there is no other meaning, itself is calm, itself is summer and night, itself is the reader leaning late and reading there.”

Put simply, Stevens’ verse demands the very stillness it describes. To appreciate its depth, you need the quiet focus it exalts. Nicholas Carr echoes this sentiment in The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains, explaining how sustained attention creates a channel through which ideas imprint themselves on the mind. In this focused state—what Stevens likens to the “summer night” of engaged intellect—writer and reader meld into “the conscious being of the book.”

This kind of immersive reading transformed academia. Works like Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire drew readers into sweeping histories of civilisation. Hume, Locke, Kant, and Nietzsche invited readers into dialogues that reshaped thought. Science, too, evolved: Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica laid the groundwork for classical mechanics, while Hawking’s A Brief History of Time redefined our understanding of the cosmos.

The printing press, in effect, set the stage for a grand intellectual partnership between writers and readers. Writers filled pages with intricate ideas and deep emotions, challenging readers to grapple with, reflect on, and reinterpret their words. This dynamic tension caused a creative explosion. Readers were no longer passive recipients; they became active participants, engaging with texts to draw their own insights and expand the conversation.

8. The End of Deep Reading? How The Digital World Is Reshaping Our Minds:

Today, we stand at another crossroads, reminiscent of the one faced during the late Middle Ages. For over five centuries, the printing press formed the foundation of our intellectual landscape, shaping how we thought, learned, and communicated. Even as the 20th century brought new technologies—radio, film, television—none could dethrone the printed word. Books remained at the heart of cultural life—for a time at least.

But now, the digital age has arrived, driven by smart devices and the internet, and it is reshaping how we engage with the written word in myriad ways. Language scholar Walter Ong called this “technologizing the word.” Once digitized, words take on a new existence. Our screen-dominated world demands a different kind of intellectual engagement, as reading evolves from a linear, reflective experience to a hyperlinked, interactive one.

“Constantin was deep in concentration. Upon the lectern he kept in his dayroom—he always stood to read—was an ancient battle saga from the central library. Despite its archaic and somewhat sanguinary nature, he was thoroughly engrossed. There were echoes of the present in the exploits of these long-gone tribes. Such savagery he had seen from the traitors—particularly the XII Legion—that he had become somewhat single minded in seeking out historical examples of the same. What education he might gain from this activity he was not sure. But he had come to look forward to the brief times he had for reading. For all his cold manner, Constantin enjoyed his stories.”

—Guy Haley | Pharos

Imagine knowledge as a great river, once flowing smoothly through the structured course of books. The printing press served as its main artery, carrying human thought in a steady, focused stream. But today, that river has fragmented into a sprawling delta, branching into countless digital streams—Instagram, X, newsfeeds, Substack—each twisting, merging, and diverging with dizzying speed. Our mental landscape has fundamentally shifted.

Whereas reading once required full immersion, today’s digital world pulls us into a web of instant connections. We jump from link to link, absorbing fragmented bits of information rather than diving deeply into any single source. Our habits are evolving to keep pace, adapting to this fast, scattered, and multidirectional flow. It’s a defining moment in our intellectual history—one I intend to explore further in an upcoming article.

10/1

Truly talented and deserve a lot of recognition . This is such a well written article focusing on the history of writing and the impact it had on culture and civilisation . Enjoyed reading this full of memorable quotes 10/10 !!!!!