1. How We React, Matters

None of us can anticipate how misfortune will strike. Prison movie Shawshank Redemption looks at one such example. Andy Dufresne is an innocent man, sentenced to jail for the double murder of his wife and her lover. The first two years were harsh on him. He was targeted by the Sisters, a gang of prison rapists and ignored by many of the other inmates.

“Bad luck, I guess it floats around,” Andy muses, fifteen years later, “it’s got to land on somebody. It was my turn, that’s all. I was in the path of the tornado… I just didn’t expect the storm would last as long as it has.”

But the film shows it’s how we respond that matters. Andy decides not to lose hope—it takes him fifteen years, but he manages to chisel his way out of prison. And during that time, he lobbies for the construction of a new prison library, and works to improve the lives of many of his fellow inmates. In the closing scene, we’re there with him as he drives his red 1969 Pontiac GTO on his way to Zihuatanejo, Mexico, and freedom.

Hardship is inevitable. From minor difficulties to the types of setbacks that sully our horizons like late afternoon thunderstorms. From small annoyances to the miscarriages of justice like those Andy was dealt.

The truth is, like it or not, we all have to face up to adversity in one form or another—and when we do, we might find Andy Dufresne’s calibre of tenacity comes in handy. Without it, like those ancient Pompeiians waking up one morning, only to find Mount Vesuvius waking up beside them, we could find ourselves prone to sudden and catastrophic changes in circumstance.

And I think this raises an important but often overlooked question. Why do some rise, amid difficulties, while others fall? “We glory in our suffering, because we know that it produces perseverance,” wrote the apostle Paul, in a letter to Rome. “Perseverance produces character; and character, hope.” Tragedy teaches us this; it tells us suffering can help us grow. It invites us to respond with patience and courage. It reminds us that, when the chips have fallen—how we react, matters.

2. The Importance Of Meaning

“The way in which a man accepts his fate, and all the suffering it entails; the way in which he takes up his cross,” writes Austrian-born Holocaust survivor, Viktor Frankl, “gives him ample opportunity—even under the most difficult circumstances—to add a deeper meaning to his life. Everything can be taken from him, but one thing,” he continues: “The last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances.”

No doubt pain can be devastating. But as Frankl intimates, it creates the space for new meanings and identities to emerge and for those identities to coalesce into something stronger, and more powerful, than what was there before.

Trapped within his concentration camp, Frankl drew strength from the memory of his wife. “Grey was the sky above; grey the snow in the pale light of dawn. Grey the rags in which my fellow prisoners were clad, and grey their faces,” he writes in Man’s Search for Meaning. “But as I conversed silently with my wife, I sensed her spirit piercing through the enveloping gloom. More and more, I felt she was present, that she was with me. The feeling was very strong: she was there.”

“In some ways suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning, such as the meaning of a sacrifice.”

—Viktor E. Frankl

The meaning we extract from circumstances often decides whether we wilt underneath them, or rise up above. That said, meaning can be a tricky thing to generate in a pinch. Reservoirs of psychological strength like this normally take a long time to establish; typically coming from a complex mesh of relationships, identities, and beliefs, developed over the course of years.

While I explore this phenomenon more in another article; here I want to focus on a more practical type of strength: something that can be established by laying down a few simple habits.

3. Defiance In The Face Of Overwhelming Odds

In 1565, Jean de Valette and his band of 500 Knights Hospitaller found themselves stationed on the fortress island of Malta: a strategic location that lay between Christendom and the Ottoman Empire. That said, few of the Knights expected the arrival of an army of 40,000 enemy Ottomans in late May. I doubt, upon seeing the sheer size of the invading forces, many of them fancied their chances. Despite this, they made their stand and waited for reinforcements. What followed was one of the most savagely contested struggles that took place during the sixteenth century.

Over the ensuing four months, the Turks, with some 65 siege guns, proceeded to blow much of the defences to rubble—overrunning Fort St. Elmo in the process. The Crusaders lost some of their bravest captains in its defence, but ultimately, the Knights held onto the island and ‘The Great Siege of Malta’ went down into legend: a heroic brotherhood of warriors, who withstood impossible odds in the defence of Christendom. Nearly two hundred years later, Voltaire quipped “rien est plus connu que la siege de Malte” (nothing is so well known as the Siege of Malta).

I don’t pretend we can equal the fortitude of such men, we live in more benign times. Practically speaking, however, there are certain lifestyle choices that, over time, can propel us in the same direction: techniques based on straightforward science, rather than convoluted articles of faith.

I want to focus on these techniques, on behaviours that we can control, that we can adapt to any given situation. And while we may never be able to fully rival the courage and resolve of men like Viktor Frankl, and Jean de Valette—we can certainly aspire to become more like them.

4. Hormones: The Ticket To Toughness

“God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,” recite participants in Alcoholics Anonymous, “and the courage to change the things I can.” Luckily for us, hormones fall into this second category—and learning how to manage them can be the ticket to overcoming adversity.

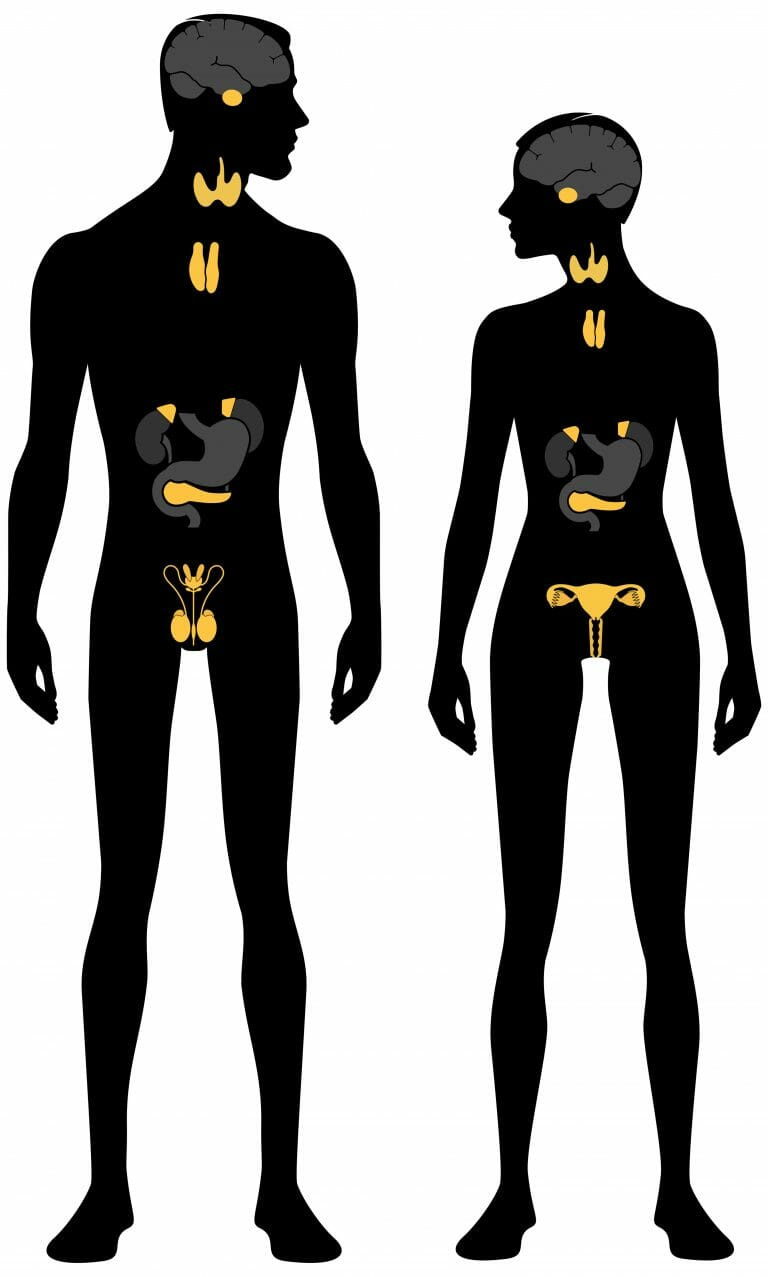

Hormones, simply put, function as our body’s chemical messengers. They get secreted into the bloodstream and transported to organs—including the brain—where they help regulate our mood and behaviour.

Indeed, minor fluctuations in their quantities jar us from whatever is on our mind and get us moving—physically and mentally—in an altogether different direction. We might, for example, be walking down the street and notice an attractive girl out of the corner of our eye. Or maybe, we’ve just finished a heavy weights session at our local gym.

Hormones play the role of behavioural catalysts in both situations—responsible for generating rapid shifts in our mood and outlook. In fact, whether it be serotonin or somatostatin; calcitonin or cortisol, these chemicals shape our desires and wants, our capabilities and personal resources; even affecting our political beliefs. More than anything, however, they define our reaction under stress—and it’s for that reason that we will be paying them more attention.

5. The Übermensch

In 1883, the German philosopher Nietzsche bestowed his concept of the Übermensch upon the world: a being able to rise above common mediocrity, and impose his will upon the Universe. A man who, Nietzsche would go on to explain, inspires greatness in others, through both his intellect and physical strength alike. Beyond such noticeable qualities, however, there would have been something else that singled the Übermensch out from the rest of society. Namely, his endocrine system—the network of glands responsible for adjusting his hormone levels.

In simple terms, the endocrine glands rally bodily functions during times of stress. They generate the chemicals we need to deal with difficulty: compounds like catecholamines, and glucocorticoids; growth hormone, and prolactin; which, when taken together, generate drastic improvements in both psychological and physiological functioning. On a short-term basis, fluctuations in these chemicals can reduce reaction times, and heighten mental alertness; while on a longer timescale they boost stamina and resilience.

So, then, can we fine-tune our endocrine system? Can we bolster hormonal output, boosting both mental and physical resolve?

The answer turns out to be yes—on both counts. Everything from our thyroids to our adrenals, and yes; even our testes, are affected by how much, and in what ways, we use them. You see, more than anything, the endocrines respond to how they’re being used—to lifestyle considerations.

The more we live life on the front foot—the more we seek out challenges and face up to pressure—the more potent and flexible these glands turn out to be, and the more energy, and personal resources, they generate for us in the future. Introduce danger and hardship, in the right amounts, and the endocrines adjust themselves accordingly.

Scientists have discovered, for instance, that rats exposed to stressful situations, over a long-term basis, went on to develop larger adrenal glands and, as a result, were able to deal with stress more effectively. Give those same rats a lifestyle of idle luxury, and transient pleasure, on the other hand, and their general hormonal decline was all but assured.

“To those human beings who are of any concern to me I wish suffering, desolation, sickness, ill-treatment, indignities — I wish that they should not remain unfamiliar with profound self-contempt, the torture of self-mistrust, the wretchedness of the vanquished: I have no pity for them, because I wish them the only thing that can prove today whether one is worth anything or not — that one endures.”

—Friedrich Nietzsche | The Will To Power

Nietzsche’s Übermensch would have crafted his superior temperament by following these same exact principles. Not, in other words, through privilege or luck—as some may suggest—but because of struggle; because of the types of situations he faced and how he chose to deal with them.

By striving against painful and often frightening conditions, his endocrine system would have gradually equipped him with the types of resources needed to conquer his own lower nature—his innate laziness and desire for comfort—and, in doing so, would have chiselled him into something more admirable, a sort of burning away of dead wood.

6. The Modern Man

Modern men, on the other hand, tend to be quite different. Their biggest threat likely comes from dealing with their girlfriend on a bad day, or leaving their smartphones behind in the office. Bounded up by material comfort and mental idleness, these guys rarely find themselves in a physical confrontation or life-threatening struggle. As a result, their endocrines have grown slack: incapable of helping them surmount serious difficulty.

Put simply, these men lack the inbuilt constitution needed for a struggle: the glands responsible for regulating their hormones have grown accustomed to function within much tighter ranges than, say, those of the Übermensch.

Misfortune, when it does strike, is often met with disproportionate and excessively emotional responses. Much like turning on sports mode in a car, without being able to handle the excess horsepower, these types of guys end up mismanaging their bodily dynamics badly: generating chemical imbalances in the process that, in the end, wreak havoc on their long term health.

For example, stress hormones like adrenalin and cortisol tend to linger in the bloodstream, interfering with their ability to relax. Mental function deteriorates and health problems begin to arise. The American Medical Association now estimates that stress plays a role in more than 60% of modern day diseases.

How, then, does the modern day ‘soy-boy’ reclaim his virility? The answer is simple. Much like doing up a dilapidated house, he must reinvigorate his degraded endocrine system. Modern society never taught him how, in fact it taught him the opposite. Raised on a lifestyle of transient pleasure and comfortable living, it encouraged him to sabotage the system of glands responsible for maintaining his mood and motivation, his focus and resilience. But, by turning this dynamic around, by rebalancing his hormones, he can change all this: he can learn how to cope with stress and recapture the dignity his predecessors once held. Society never taught him how—but I will.

7. How to Create a Toughening Regime

First off, he has two possible paths ahead of him. One is called proactive toughening. It involves things like aerobic exercise or strength training, activities that trigger physiological stress responses from within the body. So far, then, so familiar. But what’s less well known and potentially more potent is the second path—passive conditioning.

“I love to wade and flounder through the swamp,” wrote Henry Thoreau in 1854, “on these bitter cold days when the snow lies deep on the ground.” Passive conditioning challenges us to proactively mix up our environmental stimuli in ways that trigger a stress response. Physical shocks like cold water, for example, release a cascade of stress hormones into the bloodstream, which, in turn, flushes out the physiological clutter: leaving us feeling invigorated and refreshed.

Cold showers may be one option; scary social situations are another: instigating interactions with strangers, for instance, tends to trigger chemical fluctuations that vary slightly from physical exercise, but can be equally effective in terms of adapting to stress, as, say, running 6km in hot weather.

So, the next time you’re out in a bar with friends, talk to the pretty dark-eyed stranger who’s making eyes at you from across the room. If you’re anything like me, it will trigger a similar type of chemical response as cold water: leaving you feeling energised and stronger afterwards, whether you get the number or not!

The key point here is to introduce manageable adversity into your life—on multiple fronts. Physical pursuits, like running or weight training, trigger a different cocktail of stress hormones than passive ones, like bathing in cold water or flirting with hot women. Both types of activities, however, are important for sculpting a well-rounded individual.

I personally recommend salsa lessons: an activity offering a lethal combination of high paced socialising, physical exertion, and sensual intimacy. Stimuli that will, in turn, provoke a range of feel-good hormones, such as oxytocin and arginine-vasopressin, alongside more generalised stress-chemicals, like adrenalin and cortisol.

In essence, diversifying your toughening regime is going to allow you to remain flexible across many different fronts. It creates something I like to label “depth of resilience.” Like a highly trained F-32 fighter pilot, your endocrine system becomes proficient in making the countless minor chemical fluctuations needed to perform well across a variety of situations. Toughness is, after all, built on being able to handle a variety of different challenges. You don’t want to become too reliant on any one particular thing.

“Nothing in the world is worth having or worth doing unless it means effort, pain, difficulty… I have never in my life envied a human being who led an easy life. I have envied a great many people who led difficult lives and led them well.”

—Theodore Roosevelt

In fact it goes even further than this, because studies have shown optimising hormonal output boosts both cognitive, and physiological longevity. Toughening ourselves, put differently, helps safeguard the mind from the damaging effects of age and chronic stress—two things that have become very prevalent in the modern world.

Fine-tune your hormones, in other words, and you’re on the way to becoming your very own version of the Übermensch. So, then, what are you waiting for?

8. Don't Overdo It—Burnout & Exhaustion

A couple of words of caution, however, before you begin. Say, for example, you’re a stressed-out father, trying to juggle multiple work and family commitments. Or maybe an overburdened student, drowning in thousands of dollars’ worth of debt. Surely you’re becoming stronger, right? Wrong. Maxed out endocrines—without adequate periods of rest—cause stress hormones to go haywire.

Sustained catecholamine release, for instance, will trigger headaches and weight loss. Excessive cortisol, on the other hand, makes it difficult to sleep at night. Too much vasopressin, meanwhile, leads to high blood pressure.

Collectively, these high stress situations lead to what’s known as ‘allostatic load’—that is, the chronic bodily wear and tear arising from the repeated and prolonged triggering of stress chemicals. Eventually, such issues aggregate into larger problems, like diabetes and heart attacks, and you’ll find studies and work are the least of your concerns!

Add to that an interesting study comparing the health of soldiers from the second world war with those of the Vietnam war. Researchers found the hearts of Vietnam soldiers were in much poorer condition than those who fought during the second world war—indeed these men’s hearts were in a similar condition to 50-year-olds who had never seen combat.

The researchers worked out that, while the second world war veterans had seen intense and traumatic periods of fighting, they also enjoyed extended periods of rest and recovery, whereas the younger Vietnam veterans had seen enemy fire almost every single day. The extended stress, it turned out, had far more damaging and permanent effects on their health.

The important thing, then, is to give yourself adequate periods of rest between different challenges—be they mental or physical in nature. I can’t emphasise this enough—taking on too much hardship, without proper down time, will set you back further than if you’d never bothered in the first place.

Consider severity also. Particularly horrifying experiences, physical assault for instance or sustained periods of bullying, can lead to trauma. People harbouring this affliction tend to push unresolved problems to the back of their minds, only to have them manifest themselves in other ways; causing hormone spikes and health problems.

The simple truth, then, is how we manage stress ultimately depends on a whole host of factors: from social networks, to psychological maturity. Hormones, however, are one thing that we do have direct control over. Constructing an adequate training regime—one capable of optimising their production and fine-tuning regulation—will pay us back dividends in the long run: allowing us to deal more effectively with stress, take on bigger challenges, and avoid suffering from long-term health problems. What’s more, it leaves us in a better position to protect those we care about—and that’s important too.

9. Masculinity In The Modern Age

It’s fair to say that mental resolve in the modern world has somewhat collapsed. By removing everyday hardships, we’ve rendered ourselves largely incapable of facing up to larger ones: 24-hour comfort, sedentary lifestyles and round-the-clock distraction have, taken together, eroded hardiness when compared to previous generations.

Consider this for example: testosterone levels in men are supposed to sit at somewhere around 617 ng/dL. In more athletic guys, like me for instance, this figure can reach well into the thousands.

However, back in 2017, Buzzfeed conducted a study on four of its male journalists and discovered that the highest level amongst them was a mere 376 ng/dL. Astonishingly, three out of these four had levels below 270 ng/dL! To put this into perspective, this is below what you’d anticipate in an average 85-year-old man!

This study, and others like it, raise serious questions. Can men today be compared to those that came before—men like Jean de Valette or Viktor Frankl? Moreover, can these modern day ‘Buzzfeed types’ even be considered real men at all? I doubt it. Perhaps we’d be better off establishing a new sub-species altogether—how about homo-modernis? Or better still homo-descensus?

Pundits at the Guardian—who admit to having similarly low T-levels—are keen to discount such trends as inconsequential. “The idea that any kind of crisis of masculinity has been caused by lower testosterone in the population is a fiction,” one of them professes, “wished into existence by those peddling right-wing pseudoscience.”

It seems to me that such commentators would prefer to spend their time stoking moral panics, or engaging in debates, whose answers could, at bottom, be of consequence only to anyone assured of eternity. Put simply, hormones are much too practical for them.

But broader implications of these discoveries are nonetheless concerning: Men, and indeed society at large, appear to be trending towards a state of diminished capability and increased dependency. It may be hard to discern amid the technological noise—but a deeper examination reveals some truly disconcerting biological shifts.

It speaks to something else as well: the truth is that masculinity—more so than femininity—is not simply dished out at birth. It must be earned. Rollo Tomasi, a well-known masculinity blogger, describes how manhood is developed through a proactive engagement with the world around us; and then refined—physiologically and psychologically speaking—through our actions and behaviour.

“I suppose sooner or later in the life of everyone comes a moment of trial. We all of us have our particular devil who rides us and torments us, and we must give battle in the end.”

—Daphne Du Maurier | Rebecca

Even among primitive peoples, males who had failed to be initiated into tribal society—those who neglected to refine themselves in the proper ways—tended to be looked down upon.

Men weren’t considered proper men unless they’d undergone the harsh trials designed to transform them into something more. Until then, they were viewed no differently than women and children. Only once “twice-born” would these individuals be allowed to join the ranks of those who oversaw the affairs of the community.

Consider also how boys are raised nowadays, how society views manhood in general, and are the trends we’re seeing really that surprising? Concepts like equality and tolerance lead us towards perceiving weakness as moral strength. Being tolerant is seen as admirable, while being exceptional is often viewed as problematic.

In ‘Beyond Good & Evil’, Nietzsche remarked that we’ve become a society of herd animals—and he was right—nowadays we’ve become all too quick to degenerate the spirit of our ancestors, of those who once excelled, and instead seek comfort amid the crowd.

This is a problem because, as each generation gets lazier and less reliable, we’re setting the stage for a less stable world: one filled with people prone to emotional outbursts, and maladaptive stress responses. Those who can, increasingly opt to live away from this rising sense of disquiet; tucking themselves into gated communities and suburban enclaves. The rest of us, however, are left stranded to deal with the devolving social scene on a more direct front.

Perhaps even more disturbingly, many younger people seem to be retreating from the outside world altogether: captivated by 24-7 entertainment, fast food, and pornography; the next generation is calling it quits on building families, careers, and in some cases, even friendships.

My plea to you is to buck the wider trend. Use this initiative—and The Lifestyle Roadmap in particular—to redefine yourself into something more, and then use that newfound sense of self to redefine your situation. Beyond the physiological dividends, like better health and longevity; lie the psychological ones: like carrying yourself with more self-respect; and casting away the apathy and depression that previously weighed you down.

“I guess it comes down to a simple choice,” Andy Dufresne muses near the end of Shawshank Redemption, “get busy living, or get busy dying.” And that’s damn right. One day, you might look back on this article as a fork in the road: one you needed to take to become the biggest Übermensch you could possibly be. Who knows, when that happens, I may be there to greet you as a fellow traveller on the road. Until then—I wish you the best.

Read Next: When Pleasure Leads To Happiness—& When It Doesn’t

The post Hormones & Hardship: Why Do Some Rise, Amid Difficulties, While Others Fall? appeared first on Lifestyle Harmonics.

So engaging so well written you are a true modern Aristotle

Viktor Frankl is about my 4th favorite Jew and there's alot of 'em to love so that's like high praise